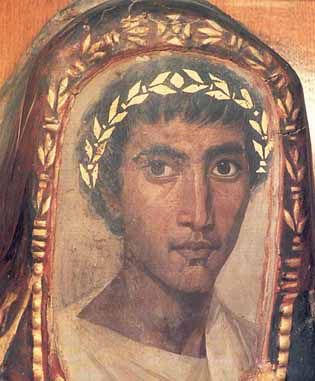

Artemidorus

[Artemidorus was surnamed Ephesius, from Ephesus, on the west coast of Asia Minor, but was also called Daldianus, from his mother's native city, Daldis in Lycia.]

[Artemidorus was surnamed Ephesius, from Ephesus, on the west coast of Asia Minor, but was also called Daldianus, from his mother's native city, Daldis in Lycia.]

Artemidorus (flourished 3rd century ad, Ephesus, Roman Asia [now in Turkey]), soothsayer whose Oneirocritica (“Interpretation of Dreams”) affords valuable insight into ancient superstitions, myths, and religious rites. Mainly a compilation of the writings of earlier authors, the work’s first three books consider dreams and divination generally; a reply to critics and an appendix make up the fourth book. He was reputed to have written books on interpreting bird signs and palm reading, but they have been lost.

Encyclopaedia Britannica

"The work of Artemidorus Daldianus on the interpretation of dreams enjoys a well-deserved neglect."

Such was the view expressed by Russel Geer of Brown University in The Classical Journal for June 1927. Professor Geer added, concerning this "laborious, pseudo-scientific effort of the second Christian century":

It is based on the assumption that all dreams, except those which clearly reflect the regular occupations or physical condition of the dreamer, are sent by the gods and, if properly understood, are unfailing indications of some future event.

Francis Barrett, who sympathized with the occult enough to write a lengthy book on "secret knowledge" titled The Magus (London, 1801), thought Artemidorus was too credulous:

That isn't to say dreams are meaningless. They, or at least some of them, probably are significant for the person who experiences them. I doubt any psychologist has a clue about a client's dreams. Only the individual holds the key to his own dreams, and most of us have misplaced our keys.

I bring up poor old Artemidorus not to defend his dream interpretation theories, but to defend him -- and by extension, many thinkers of the ancient world -- from our contemporary notion that they all (with a generous exception for Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle) were ignorant, unscientific, and superstitious.

Robin Lane Fox discusses Artemidorus in his remarkable book Pagans and Christians. Its depth of scholarship is astounding -- he even seems to have read the Oneirocritica in its entirety, something hardly anyone in our time has done -- but Lane Fox writes smooth, intelligible English, unlike so many of today's young academics.

One of the virtues of Pagans and Christians is that the author doesn't reduce the story of Christianity's growing hold on the Roman empire to political terms. He understands that it was a divergence and conflict between different ways of perceiving the world, centering not around dogma -- the pagans had none -- but around modes of consciousness.

For example, Lane Fox devotes quite a few pages to the long tradition, stretching back to Homer, of individuals seeing and hearing their favorite gods not just in dreams but while awake. He gives enough examples to be convincing that direct communion of gods was uncontroversial (except among Christians) and continued until the very twilight of paganism.

(My own thought on this, based on a limited understanding but considerable reading, is that non-corporeal spirits -- especially those of a higher type -- appear to those of us on the earth plane in a form we can understand or appreciate. Thus, Christians have visions of saints or Jesus himself; Romans and Greeks in their part of the empire saw and heard elevated spirits in terms of their favorite among the polytheistic committee. I don't believe visits by spirits are any less frequent now than in the early days. The difference between people in our time and those in the ancient world is that back then they could express the manifestations with no fear of scorn, while in our spiritually broken days, to describe such apparitions is to risk being taken for a nut.)

Wisely, he doesn't try to weigh the truth or meaning of such experiences. He simply takes a phenomenological view: this is what people said happened to them.

Anyway, Lane Fox goes to some trouble to counter the idea that Artemidorus was a crackpot. The ancient dream interpreter's methodology deserves to be called scientific. From Pagans and Christians:

Of course, no modern psychologist or scientist of any stripe can be equally accused.

We find in Artemidorus some of the most trifling incidents in dreams noted by him to presage very extraordinary things; such, as if any one dreams of his nose, or his teeth, or such like trifling subjects, such particular events they must denote.

Now, as we cannot attribute a true and significant dream to any other cause than the celestial intelligences, or an evil dæmon, or else to the soul itself (which possesses an inherent prophetic virtue, as we have fully treated of in our Second Book of Magic, where we have spoken of prophetic dreams), I say, from which of these causes a dream proceeds, we must ascribe but a very deficient portion of knowledge to either of them, if we do not allow them capable of giving better and plainer information respecting any calamity or change of fortune or circumstances, than by dreaming of one's nose itching, or a tooth falling out, and a hundred other toys like these ... [Long-winded, in the manner of Barrett's time, but reasonable and cleverly said.]I've read a few scraps of Artemidorus's Oneirocritica -- just quotations -- and they strike me as nonsense on stilts. (Of course, it isn't fair to judge a huge body of work based on scraps.) But his theories seem no sillier than those of Freud or any other modern interpreter, including the sainted Jung. Full disclosure, I'm a dream interpretation conscientious objector.

That isn't to say dreams are meaningless. They, or at least some of them, probably are significant for the person who experiences them. I doubt any psychologist has a clue about a client's dreams. Only the individual holds the key to his own dreams, and most of us have misplaced our keys.

Robin Lane Fox discusses Artemidorus in his remarkable book Pagans and Christians. Its depth of scholarship is astounding -- he even seems to have read the Oneirocritica in its entirety, something hardly anyone in our time has done -- but Lane Fox writes smooth, intelligible English, unlike so many of today's young academics.

One of the virtues of Pagans and Christians is that the author doesn't reduce the story of Christianity's growing hold on the Roman empire to political terms. He understands that it was a divergence and conflict between different ways of perceiving the world, centering not around dogma -- the pagans had none -- but around modes of consciousness.

(My own thought on this, based on a limited understanding but considerable reading, is that non-corporeal spirits -- especially those of a higher type -- appear to those of us on the earth plane in a form we can understand or appreciate. Thus, Christians have visions of saints or Jesus himself; Romans and Greeks in their part of the empire saw and heard elevated spirits in terms of their favorite among the polytheistic committee. I don't believe visits by spirits are any less frequent now than in the early days. The difference between people in our time and those in the ancient world is that back then they could express the manifestations with no fear of scorn, while in our spiritually broken days, to describe such apparitions is to risk being taken for a nut.)

Wisely, he doesn't try to weigh the truth or meaning of such experiences. He simply takes a phenomenological view: this is what people said happened to them.

Thanks to one author, we happen to know the dreams of the early Antonine age better than any before or after in antiquity. In five remarkable books, Aremodorus of Daldis explained his theory of dreams' significance, the meanings of their common types and how, in his experience, the accepted meanings had turned out to be true. His interest was in dreams' predictive power, not in their "analytical" relevance to diagnoses of a person's past or present.Artemidorus was not easily enlisted into the ranks of soothsayers with simplistic explanations.

He had spared no efforts to find out the truth. He had read his predecessors' books and developed theoretical distinctions of his own. He had associated with the despised "street diviners," with whom he had swapped experiences, and he had also visited the major games and festivals of "cities and islands" from Italy to the Greek East, where he had questioned the spectators and competitors, the athletes, rhetors and sophists who attached such interest to dreams of their personal prospects. ...

Research and observation, he insisted, were essential to the dream interpreter's art. In each case, he had to consider local custom, the oppositions of custom and nature and the dreamer's previous thoughts and wishes.Lane Fox obviously admires Aretemidorus, but acknowledges that the ancient researcher could not quite avoid the assumptions of his time and place: "The dreams of athletes and performers from his own Asia, the curious local cults of Dionysus, the various types of bullfighting and bull-leaping, the small cult associations, or symbioseis, which we find in his own Lydia -- all this evidence he had to fit to his theories, and he shows the dogmatist's strong resentment of criticism and disbelievers' 'envy' as he struggles to make his theory fit."

Many dreams were not predictive, because they merely duplicated thoughts and wishes in the dreamer's own mind: sometimes, Artemidorus had had to discover details of his clients' sex life in order to predict the meaning of their dreams correctly. [Freud long before Freud!]

Of course, no modern psychologist or scientist of any stripe can be equally accused.

The smartest men and women of antiquity were no stupider than we are. Of course they lacked our technology, or in some cases any practical development of it. But they were alive to facts of existence that our so-called public intellectuals won't lower themselves to take seriously: the ancients of the Western world (not to mention those of other cultures) were in touch with levels of reality our scientific-materialist cognoscenti are blind and deaf to. We live far more comfortably, and I'm the last to put that down. But many of them lived more deeply.

1 comment:

Apropos of nothing, how are your cats doing?

There has been no change in my luck overall (I prefer the Chinese point of view that black cats represent good luck myself) other than wildlife.

I found feathers, and they have been outside, it seems they managed to get the bluebird of happiness.

And yes Rick, I will miss him.

Post a Comment